Machine learning is often taught through a long list of algorithms: linear regression, decision trees, random forests, neural networks, clustering methods, gradient boosting, and many more. For beginners, this can quickly feel overwhelming, as if machine learning is simply a toolbox of unrelated techniques.

But in practice, machine learning is far more structured than it first appears.

Most machine learning models used in real organizations belong to a small number of problem families. These families are not defined by the name of the algorithm, but by something more fundamental:

The type of output the model is designed to produce.

This is one of the most important organizing principles in machine learning.

Before asking which algorithm should we use, we must first ask:

A model that predicts a number is fundamentally different from one that predicts a category. A model that discovers groups is different from one that ranks options. A model that forecasts future demand operates under different assumptions than one that classifies fraud.

Thus, machine learning begins not with algorithm selection, but with problem formulation.

In real-world AI systems, the most common reason machine learning projects fail is not because the team chose the wrong model architecture.

It is because the problem was framed incorrectly.

For example:

The type of machine learning problem determines everything downstream:

Choosing the correct model family is therefore one of the most critical decisions in applied machine learning.

In the previous chapter, we defined a machine learning model as a learned function:

y^=f(x)

Where:

If machine learning is fundamentally about learning functions, then what kinds of outputs can these functions produce? The key question thus becomes:

What form does y^ take?

This is one of the most important organizing principles in the field:

Machine learning models are best understood not by their names, but by the type of output they generate.

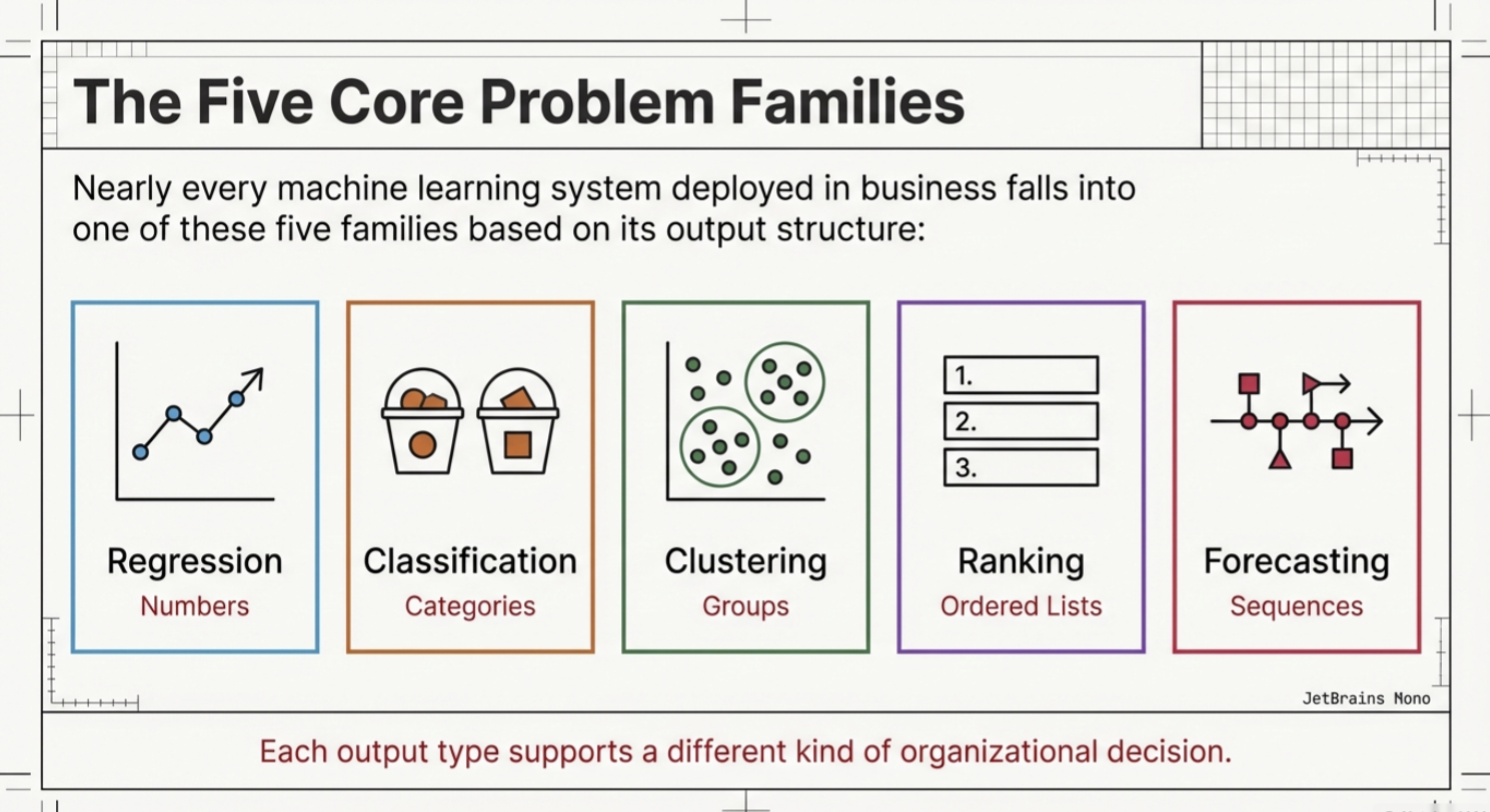

In practice, nearly every machine learning system deployed in business falls into one of five broad problem families:

Different machine learning problem types correspond to different output structures:

Each output type supports a different kind of organizational decision.

For example:

Thus, machine learning models are not abstract mathematical objects.

They are decision engines embedded in business systems.

Nearly all applied machine learning systems fall into one of the following five families:

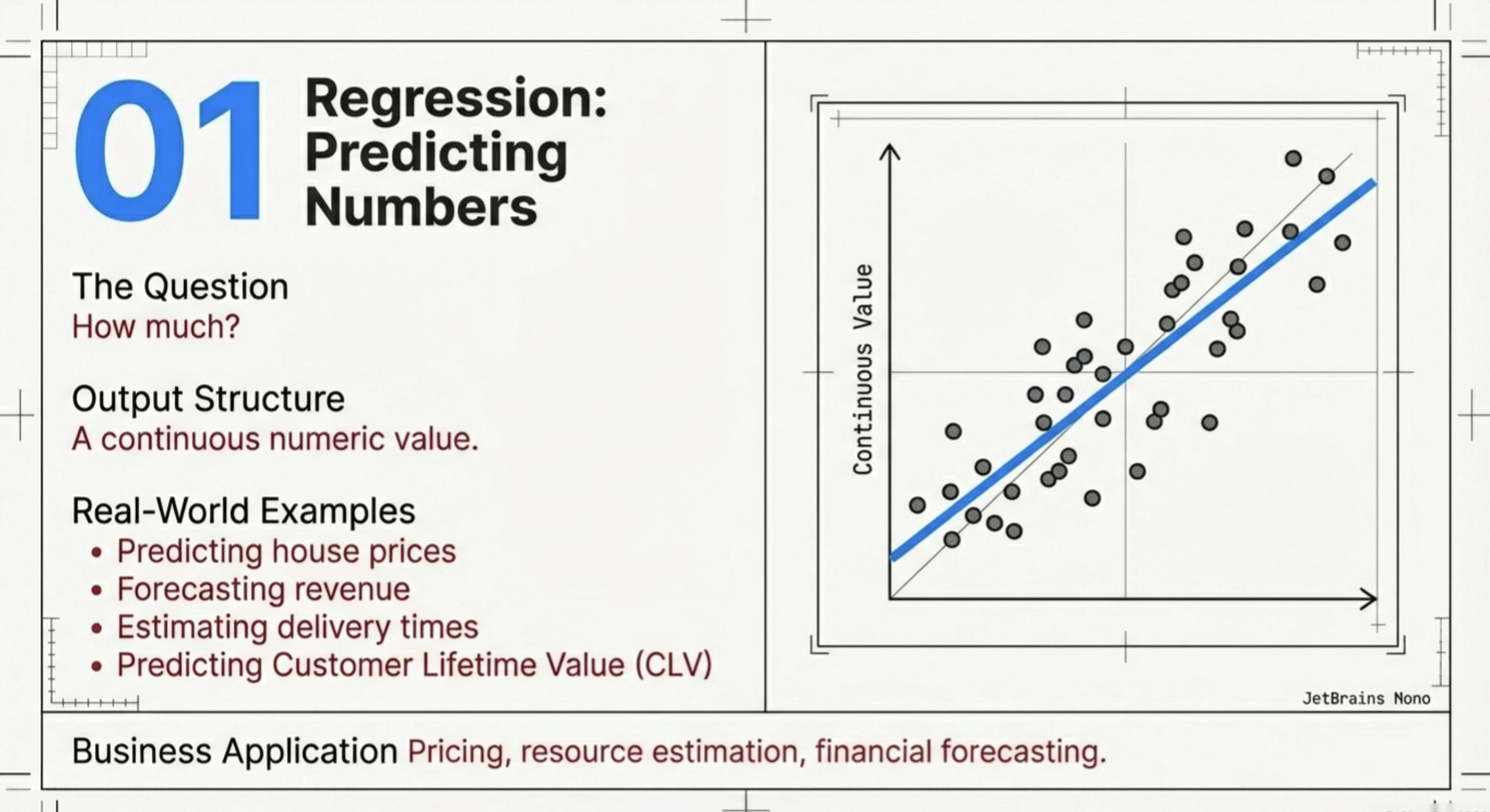

3.2.1. Regression — predicting numbers: Regression models are used when the output is a continuous numeric value. Examples: predicting house prices, forecasting revenue, estimating delivery time, predicting customer lifetime value

Regression answers the question: How much?

3.2.2. Classification — predicting categories: Classification models are used when the output is a discrete label or class. Examples: fraud vs non-fraud, churn vs retained, spam vs legitimate email, disease present vs absent.Classification answers the question: Which type?

3.2.3. Clustering — discovering groups: Clustering is an unsupervised learning problem where there are no labels. Instead, the model identifies natural groupings in the data. Examples: customer segmentation, grouping similar products, identifying behavioral cohortsClustering answers the question: What structure exists in this population?

3.2.4. Ranking and recommendation — ordering choices: Ranking models are used when the output is not a single prediction but an ordered list. Examples: which products to show first, which search results to rank highest, which leads to prioritize, which videos to recommend nextRanking answers the question: What should come first?

3.2.5. Time-series forecasting — predicting the future over time: Forecasting models are used when the data is sequential and time-dependent. Examples: demand forecasting, inventory planning, energy load prediction, financial forecasting

Forecasting answers the question: What will happen next, given what has happened before?

This chapter introduces these model families and explains why choosing the correct problem type is often more important than choosing the specific algorithm.

These problem types correspond directly to how AI creates value inside companies. A modern enterprise might simultaneously deploy:

Each family supports a different operational system.

Understanding these distinctions is what allows AI teams to design solutions that are technically correct and strategically useful.

This chapter will introduce each machine learning problem family in turn:

The goal is not simply to list algorithms, but to build a conceptual map:

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to look at any business problem and immediately identify:

After completing this chapter, you should be able to answer the most important early question in machine learning:

What type of prediction problem am I solving?

Because once the problem type is clear, model selection becomes far more structured, and machine learning becomes far less mysterious.

In the next chapter, we will study Regression Problem Family.